f l a s h b a c k s

Back in the 1970s, personal computers didn’t exist yet. Neither did the internet.

In January of 1975 I visited the legendary Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. That was my first exposure to pixels.

superpaint, 1975

In 1976 I joined NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California as its Artist in Residence.

caligari, 1978

After a while, I started building immersive worlds there.

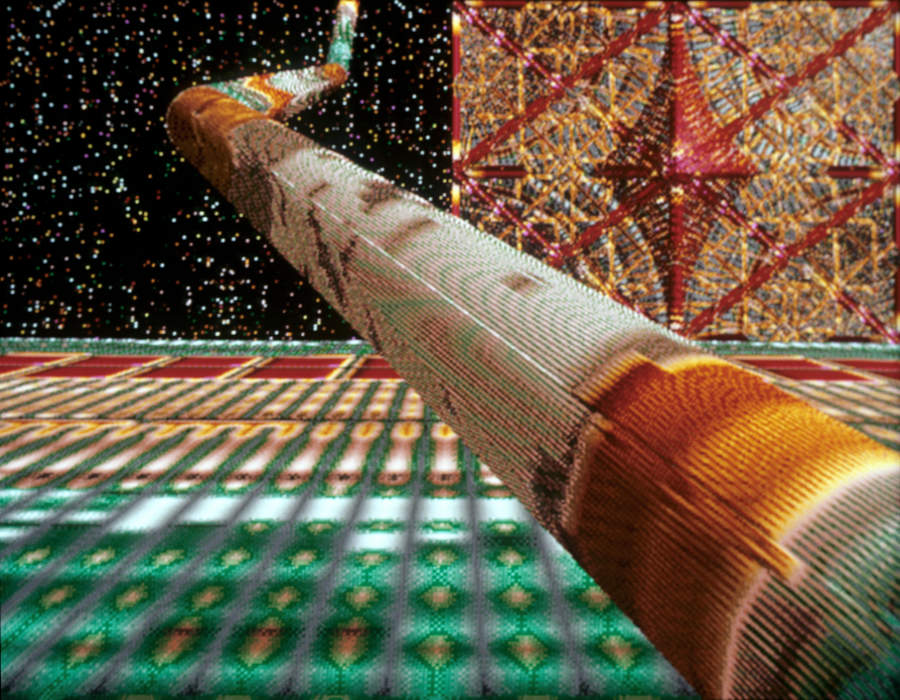

transjovian pipeline, 1979

Next I constructed generative 3D structures that evolved over time.

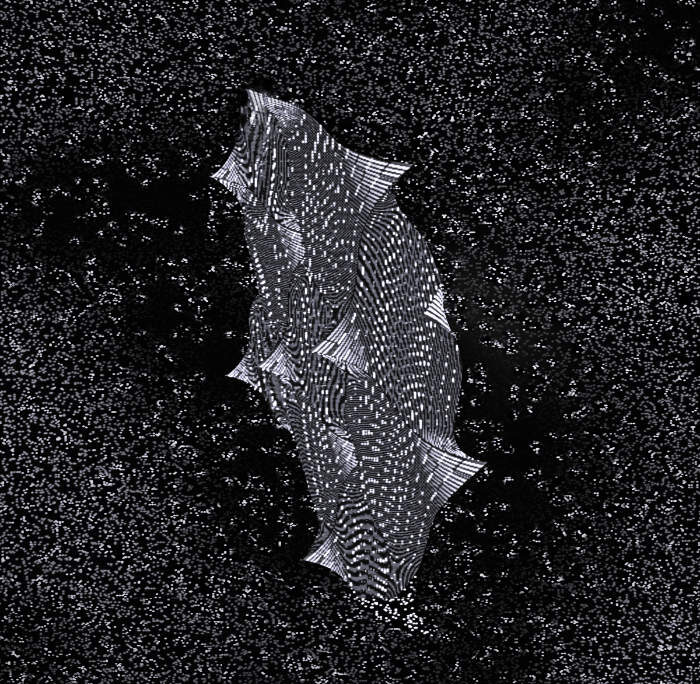

polymorph, 1988

The first artwork I produced on a desktop computer was in 1990 at Apple’s Advanced Technology Group in Cupertino.

the green mask, 1990

In the mid-1990s, I built a network of workstations in my Sierra Madre, California studio.

Perdido Street, 2016

Eventually, the world got wired up to the web, hardware and software prices fell off a cliff, and millions of artists joined the digital revolution.

Today pixels mediate virtually every aspect of our existence.

The rest is history.